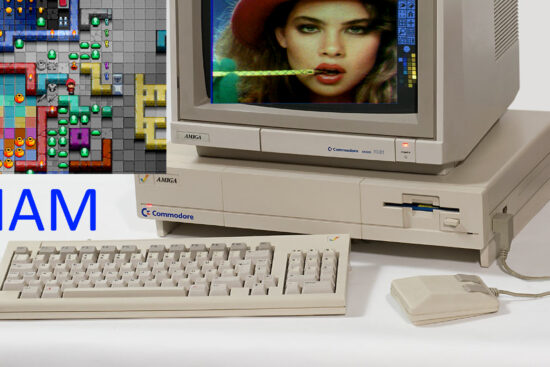

Commodore’s bankruptcy left behind a host of orphans who continue to this day to keep alive the memory of those marvellous machines that made us rejoice, and among them a prominent place is certainly that of the Amiga, because it presented features that revolutionised the “personal” computer sector.

In fact, the system was so advanced that it was even possible to have browsers to surf the Internet, which is why it is still used by thousands of enthusiasts (so not just to play some glory of the past).

Having had a substantial “hard core” is the reason why, even though the parent company went bankrupt, other companies took over its assets and intellectual property, trying to follow up on the platform. Likewise, individuals or community groups tried to make up for the shortcomings by continuing to develop software and/or hardware for the Amiga, and even re-implementations of the original OS.

This also led to the creation of factions that clashed in classic pseudo-religion systems wars, which continue to this day, albeit with less and less fervour considering the substantial stagnation due to the growing realisation that the platform no longer has any chance for the future, whatever umbilical cord sympathisers have attached themselves to.

In spite of this, among the reasons for the feuds there is one in particular that continues to ignite animosities at every opportunity: the Amiga. More precisely, what is meant by this term, given that there is a very strong tendency to (re)define it at will, in the psychological (and pathological, in many cases) need to (self)support and (self)justify the use of one’s own post-Amiga platform (by which I mean everything after Commodore’s departure).

The legal aspect

In order to bring some order to the subject, we must begin by pointing out what should be self-evident, but unfortunately is often not, judging by what we read around: who coined the term and, above all, to whom it belongs.

As history has handed us, the term was chosen by the group of inventors of the platform, and then passed to Commodore after the acquisition of their company, and was registered as a trademark, along with three others: AmigaDOS, Intuition, and Workbench.

Note that neither “AmigaOS” nor “Amiga OS” were. AmigaDOS, Workbench, and even Kickstart were used instead of or as a reference to the Amiga OS, but the OS itself did not have a name of its own.

It goes without saying, therefore, that it is the sole responsibility of the company that owns the trademark to decide which product can use it, in what way, in what context, and with what restrictions. So Commodore as long as it was alive, and subsequently the companies that took over its properties.

These seem trivial things, but judging by the rabble-rousing, it seems absolutely necessary to repeat and underline it once again: only those who own the Amiga brand have the right to use it how and where they want. Even to sell toasters with this name…

The definition

Fortunately, Commodore did not limit itself to protecting its intellectual property, but was also prodigal in publishing copious technical documentation to define quite precisely how products bearing this label were made, how they worked, and, consequently, what is defined as such.

The primary source has always proved to be the very famous (at least for developers. Hopefully) “Amiga Hardware Reference Manual“, which already has an eloquent summary on the back cover:

The Amiga Computer is an exciting new high-performance microcomputer with superb graphics, sound, and multitasking capabilities. Its technologically advanced hardware, designed around the Motorola 68000 microprocessor, includes three sophisticated custom chips that control graphics, audio, and peripherals. The Amiga’s unique system software is contained in 192K of read-only memory (ROM), providing programmers with unparalleled power, flexibility, and convenience in designing and creating programs.

But exactly the same definition can be found in all the other manuals that have been published by Commodore, which belong to the equally famous ‘”Amiga ROM Kernel Reference Manual” series. Like, for example, the Exec manual (which can be considered the Amiga kernel).

The key elements underpinning it are, therefore:

- the hardware consisting of three custom chips to manage graphics, sound, and peripherals;

- the Motorola 68000 processor;

- the (proprietary) operating system.

Further clarifications that make the situation even clearer can be found by reading the pages of the hardware manual (as we shall see later).

Unfortunately, the first edition is not freely accessible from archive.org, so I will only refer to the second and third, which are in any case sufficient to also understand how this definition evolved to cover future models.

In the meantime, it should be noted that the back cover changes slightly in the second edition:

The Amiga computers are exciting high-performance microcomputers with superb graphics, sound, multiwindow and multitasking capabilities. Their technologically advanced hardware is designed around the Motorola 68000 microprocessor family and sophisticated custom chips that control graphics, audio, peripherals, and input/output to other equipment. The Amiga’s unique operating system software provides programmers with unparalleled power, flexibility, and convenience in designing and creating programs

In short, we now speak of computers in the plural (before it was in the singular because there was only the Amiga 1000 available), and for the same reasons we refer to the 68000 family of processors and not just the 68000. Finally, instead of system software, one speaks of the operating system (but this is nothing special).

Few changes, but significant ones, because the plural conveys an expansion of the range and, thus, also outlines its future, which must of necessity be taken into account (in terms of support and, of course, programming).

The third edition is simplified, having removed only a few listed terms (what custom chips are capable of doing):

The Amiga computers are exciting high-performance microcomputers with superb graphics, sound, multiwindow and multitasking capabilities. Their technologically advanced hardware is designed around the Motorola 68000 microprocessor family and sophisticated custom chips. The Amiga’s unique system software provides programmers with unparalleled power, flexibility, and convenience in designing and creating programs.

The only difference (however insignificant) is the return to the adoption of system software instead of the operating system. The rest remains intact, also because there was no point in changing it.

At this point, however, we must reiterate what should be a truism, but is not at all (as we shall see later): the Amiga is a computer. Hardware, then. And not software. The software (the OS) is part of it (a portion was stored in a ROM), together with custom chips and a processor from the 68000 family.

The models and basic components

This is reiterated in the introductory pages of the manual, which goes into more and more detail.

The Amiga family of computers consists of several models, each of which has been designed on the same premise — to provide the user with a low cost computer that features high cost performance. The Amiga does this through the use of custom silicon hardware that yields advanced graphics and sound features.

There are three distinct models that make up the Amiga computer family: the A500, A 1000, and

A2000. Though the models differ in price and features, they have a common hardware nucleus that makes them software compatible with one another.

The third edition changes only slightly, as it adds the Amiga 3000 to the list:

There are four basic models that make up the Amiga computer family: the A500, A1000, A2000, and A3000.

The trend, however, is clear: the manual is updated because the hardware evolves, although it is based on the same foundations. This includes the custom chips that provide the common hardware for all models. And a processor based on the same family, as mentioned when the Amiga parts list is provided:

Motorola MC68000 16/32 bit main processor. The Amiga also supports the 68010, 68020,and 68030 processors as an option.

There is a small but substantial difference regarding the aforementioned custom chips. In the second edition they are not mentioned in the list of Amiga components, but immediately afterwards:

In addition to the 68000, the Amiga contains special purpose hardware known as the “ custom chips” that greatly enhance system performance. The term “ custom chips” refers to the 3 integrated circuits which were designed specifically for the Amiga computer. These three custom chips (called Agnus, Paula, and Denise) each contain the logic to handle a specific set of tasks, such as video, sound, direct memory access (DMA), or graphics.

While in the third edition they are listed immediately after the first entry (the processor entry):

Custom graphics and audio chips with DMA capability. All Amiga models are equipped with three custom chips named Paula, Agnus, and Denise which provide for superior color graphics, digital audio, and high-performance interrupt and I/O handling. The custom chips can access up to 2MB of memory directly without using the 68000 CPU.

This last issue I think is the most significant, as it inextricably cements the link between these chips and the processor: there is no Amiga without them (and without a processor from the 68000 family)!

Which, moreover, is found a little later on:

In addition to the 680×0, all Amiga models contain special purpose hardware known as the custom chips that greatly enhance system performance. The term custom chips refers to the three integrated circuits which were designed specifically for the Amiga computer.

[…]

Although there are different versions of the Amiga’s custom chips, all versions have some common features.

And that they are absolutely fundamental is greatly emphasised below:

The most important feature of the Amiga’s hardware design is the set of

custom chips that perform specialized tasks independently of the CPU.

So not only must custom chips be part of the Amiga, they are also the most important component!

An eye to the future

With the increasing number of models and, in general, the different hardware available, Commodore decided to stress the concept further in a special section of the introduction, so as to make developers more aware of the problems that can occur if they are not properly taken into account.

In particular, I quote the most significant part on this subject:

The Amiga is available in a variety of models and configurations, and is further diversified by a wealth of add-on expansion peripherals and processor replacements. In addition, even standard Amiga hardware such as the keyboard and floppy disks, are supplied by a number of different

manufacturers and may vary subtly in both their timing and in their ability to perform outside of their specified capabilities.

For this reason, the OS takes an absolutely central role, and developers are strongly encouraged to use it as the main solution:

The Amiga operating system is designed to operate the Amiga hardware within spec, adapt to different hardware and RAM configurations, and generally provide upward compatibility with any future hardware upgrades or “add ons” envisioned by the designers. For maximum upward

compatibility, it is strongly suggested that programmers deal with the hardware through the commands and functions provided by the Amiga operating system.

So we have seen that on the one hand the Amiga is defined quite precisely, with the main components being the custom chips and a processor from the 68000 family. On the other hand, it is warned against hardware evolutions (which there have also been since the first model was introduced) and is asked to switch mainly to the OS, which is in any case part of the system.

It should be underlined that this does not imply that one should not use the hardware directly and, consequently, only use the OS. More on this, perhaps, in a future article.

The Amiga’s OS does not (by itself) make the Amiga!

Staying on the subject of the OS, it must be said that it often happens to see “confusing the part with the whole“, which is a well known logical fallacy, unfortunately very common in the post-Amiga environment due to the discontinued production of these machines and with the only OS left now available (having been ported, and called AmigaOS4, to hardware equipped with PowerPC processors).

The fallacy stems from the fact that the OS is only one of the Amiga’s components, as has been amply demonstrated with plenty of details and facts, and its mere presence can never make the Amiga any other hardware.

It must be remembered once again, in fact, that the Amiga is and remains a line of computers. So we are necessarily talking about hardware, and we know that this hardware has not been produced for quite a while now.

And it is not just any hardware, as the lion’s share is made by custom chips, supported by a processor from the Motorola 68000 family (and only those!).

Yes, the OS is very important (especially in view of the future, with new hardware on the way), but it is only one of three parts. And if even just one of the other two is missing, one can no longer speak of Amiga.

Conclusions

Unfortunately, it is a concept that is perhaps too difficult to digest for a hard core of OS fanatics, who are psychologically (and pathologically, as already mentioned at the beginning) convinced that it is enough to run a port of the original OS to daydream about still using an Amiga (on a system level).

But personal problems, as well as one’s own personal beliefs, are not and will never be able to change the facts that have been reported. And, above all, they cannot change the definition of the Amiga.

Also because those who have had an Amiga in their hands know very well what they had to deal with and what satisfaction it gave. Emotions that, as we experienced them at the time, surrogates can no longer reproduce…